Play #93: Orion

The play is set in Berlin in June of 1933. Playwright Bertolt Brecht is getting ready to leave Germany for the safety of Denmark. Before he goes, he must placate or otherwise listen to the forlorn demands for affection and loyalty addressed to him by the various women in his circle—Elisabeth Hauptmann, Ruth Berlau and others—most of whom, except for his wife, Helene Weigel, were both lovers and, if you do the research, unacknowledged collaborators in the writing and staging of his plays.

As the play opens, Brecht is talking with distraught actress and writer Margarete Steffin (1908-1941)—who appears to have contributed a good deal to Brecht’s Galileo and to his The Good Woman of Setzuan. Steffin is already suffering from the tuberculosis that will kill her eight years hence. Brecht tells the unhappy Steffin that he would cheerfully divorce Helene Weigel and marry her—if only she were not ill (though he has pointedly refused all along to give her money that would help to secure her the treatment she needs—and never gets!).

[Note: What follows is derived from a single page—page 299—of John Fuegi’s still controversial Brecht & Co.: Sex, Politics, and The Making of Modern Drama (New York: Grove Press, 1994)]

STEFFIN: Why don’t you understand? I need to have something of yours while you’re gone! Some part of you to be here with me!

BRECHT (reaching into his pocket): I’m going to give you a ring. [he places three cheap metal rings on the table between them].

STEFFIN (crestfallen): There are three identical rings here. Who are the other two for?

BRECHT (irritated): What does it matter? Choose one for yourself.

STEFFIN (picking a ring, almost at random): Thank you.

BRECHT (with ersatz heartiness): There’s more.

STEFFIN (weary): Yes?

BRECHT: Yes, a second gift—this one from heaven!

STEFFIN (depleted): I don’t understand.

BRECHT: Look up at the night sky.

STEFFIN (she glances up): Yes. And so?

BRECHT (patiently): The constellation you see wheeling above us is Orion—the great hunter.

STEFFIN: Yes? But I don’t understand what you are showing me. You spoke of a heavenly gift?

BRECHT (triumphantly): This is it! From now on, while I am away, we can both look up at Orion—from wherever we are—and be joined in the heavens!!

[Steffin buries her head in her hands and weeps]

(curtain)

Play #92: Colin and Clifford, on the Road.

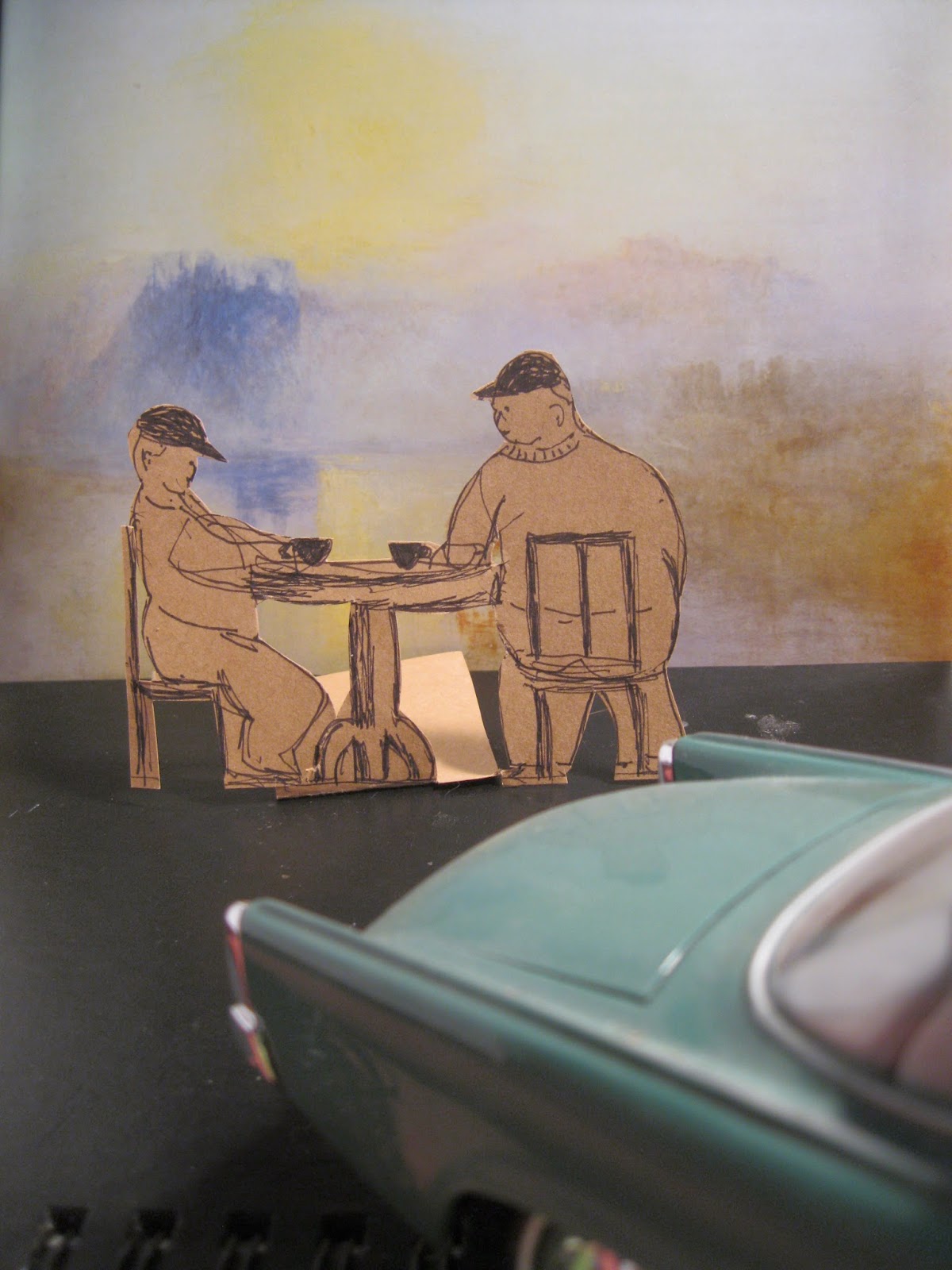

Colin and Clifford are traveling. It is the end of summer and, as the two of them sit with cups of coffee before the splendour of a roaring sunset, they begin to talk about where they’re going.

COLIN: Maybe we should push on if we want to make Tobermory before nightfall.

CLIFFORD (abstractly): I guess:

COLIN: Lots of wrecks in Tobemory.

CLIFFORD (distractedly): Glad to hear it. They’re going to love us.

COLIN: No, I meant ship wrecks. You know, under the water.

CLIFFORD: Carelessness.

COLIN: I’m sure none of them were deliberate. You know how things can go wrong.

CLIFFORD: Maybe the chamber of commerce put them there—to give the skuba divers something to find.

COLIN (wearily): Jeez, Clifford, Coffee makes you so goddam cynical!

CLIFFORD (grinning): I lean back on it.

COLIN (looking up at the incendiary sky): Some sunset, huh?

CLIFFORD (agreeing): Big.

COLIN: Yeh. Makes you feel small.

CLIFFORD: Maybe it makes you feel small. It makes me hungry.

COLIN: Okay, so we’ll go eat.

CLIFFORD (draining his cup): Right.

[a lengthy pause]

COLIN: Listen do you ever think about what happens when you die?

CLIFFORD: Never. And especially not when I’m hungry.

COLIN: Okay, well try to think of it now. I’m asking you again. What are you planning go do when you die?

CLIFFORD (off the top of his head): I thought I’d just lie on my back and look at the stars…

COLIN: But things…well, you know…there are likely to be transformations. Declensions. A dwindling of some kind.

CLIFFORD (with great finality): I’m going to lie on my back and look at the stars…until we get all mixed up together.

(curtain)

Play #91: The Wild Ass’s Waistcoat (after Balzac’s The Wild Ass’s Skin, 1831)

The play is set in the present, at the heart of any contemporary city. Its protagonist, Raphael de Valentin, is a struggling but penniless young writer and aesthete who, having failed at everything, has made one final visit to an antiques store he likes (even murderous depression cannot really staunch or quell a genuine lust for objects of virtu) before going back to his rented room kill himself.

Although Raphael has no money with which to purchase anything, the demonic antiques dealer nevertheless offers him something gratis: an exquisite vest made from an untanned wild ass’s skin. Raphael, naturally suspicious, is not so suspicious as to resist the idea that this peculiar vest might not add a touch of glamour to his otherwise sordid demise-to-come.

Raphael: Well, I scarcely know what to say.

Dealer (heartily): Yes, it’s a remarkable garment. The skin from which it is made is very old—they say it goes back to the days of King Solomon!

Raphael: It’s exquisite.

Dealer: Yes, well, wear it in good health, my boy!

[Alas for the hapless Raphael, he knows nothing of the vest’s strange and sinister secret—to whit: because the vest is a) untanned and b) magical, it offers its wearer the fulfilment of three wishes. The trouble is that with every wish the garment grants, it also shrinks substantially, each shrinking representing a shortening of the wearer’s natural life by fifteen years. If Raphael really were about to commit suicide, this might not matter, but when he discovers the vest’s enchanted generosity, suicide doesn’t seem nearly as attractive as it did before. So instead of killing himself, Raphael immediately gets rich. So far, he had made two wishes and, with the two wishes in aggregate, he moves closer and closer to death. When w see him next—rich and swell-satisfied, if a little snug about the waist—he has one wish left].

Raphael (driving his new yellow Hummer across the city with his girl de jour cosily nestled seven or eight feet from him on the Hummer’s front seat): O where will it all end?

(curtain)

Play #90: The Utopian Turtletopper

The play is set in poet Marianne Moore’s apartment in Brooklyn. It is the autumn of 1955. As the play opens, Moore is talking with Robert. B. Young, of the Marketing Research Department of the Ford Motor Company. Ford is trying to come up with a sprightly new model and, to that end, have come to ask the famous poet if she can possibly suggest a compelling name for the new car. They have helpfully provided a big photo of the embryonic vehicle, which Mr. Young has just taped to the wall of Moore’s apartment.

Moore: That’s it?

Young (proudly): That’s it. Can you help us with a name? Another Thunderbird would be fine!

Moore: Yes, I liked Thunderbird too. Well, how about The Ford Silver Sword?

Young (embarrassed): Well, I….uh….

Moore (continuing): Or The Resilient Bullet.

Young (more embarrassed): Oh I don’t think….no.

Moore (with mounting enthusiasm): The Ford Faberge!

The Mongoose Civique. The Aeroterre!

Young (weakly): Well, I guess Aeroterre isn’t too bad….

Moore (exuberantly): I’ve got it!”

Young (expectant): Yes?

Moore (triumphant): The Pastelogram!!

Young (defeated): That’s ridiculous.

Moore (still perky): Is it? Okay, here’s my very best suggestion yet.

Young (beyond caring): Great.

Moore (with barely suppressible delight): Utopian Turtletop!!

[Young buries his head in his hands]

Moore (tenderly): I see you like that one too!

(curtain)

Play #89: The Carcass of Beef

The play takes place in the threadbare Paris studio of Russian immigrant painter, Chaim Soutine, at 14 Cite Falguiere, near the Boulevard Montparnasse. It is the summer of 1922, and Soutine, desperately poor, spectacularly unkempt, grievously undernourished and aesthetically obsessed, is making a painting of an entire side of beef which, bloody and dripping, he has strung up in his studio before his waiting easel. On the morning of the play, Soutine has received a visit from his best friend, painter Amedeo Modigliani—who is every bit as hungry and as needful as Soutine is.

Modigliani (watching Soutine paint): A side of beef is pretty expensive, isn’t it?

Soutine (wearily): Fantastically. I took me months to save up enough money to pay the butcher.

Modi (gently): You could have bought food for yourself.

Soutine (pointing proudly to his almost finished canvas): This is more nourishing for me!

Modi: The carcass stinks something awful!

Soutine (calmly): Well, I work very slowly. The thing started to decay about a week after I hung it up. It’s been there a month. But isn’t it glorious?!

Modi: Chaim, the whole neighbourhood reeks of it.

Soutine (more calmly still): Well, I’m almost finished.

Modi: When will it be done?

Soutine: Today. Tomorrow. Next week. Will you help me get rid of the carcass when I’m through? It’s too big to just throw in a dustbin.

Modi: (laughing): I suppose I’ll have to, just to freshen the air. Where will we take it?

Soutine: I don’t know. Out. Away.

Modi: Away?

Soutine: Away from here.

Modi: A long way from here!!!

(curtain)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)