Brief Play #100: Promises Promises

The play is set on the stage of the Brief Candles Theatre, and, simultaneously, in the mind and, in particular, in the scratchy, threadbare realms of memory.

Bertolt Brecht: I thought something would happen.

Elizabeth Hauptmann: Why would you think that?

Brecht: Theatre used to make something happen

Hauptmann: Oh I don’t think so.

\

Hooded photographer: Hold still.

Brecht: Why?

Photographer: This is to be a memorial photograph.

Wolf (shouting from offstage): Of what? I never got to devour Little Red Riding Hood!

Red Riding Hood (from offstage): And I am still uneaten!

Salome (offstage): I shall never get this dance to come right. I need more time. So far, my stepfather, Herod, is only titillated, but not ravenous….

Woman at Laptop (without looking up): I am both titillated and ravenous.

Doctor Behind Desk: I am everyone’s doctor. And I can see that nobody is getting any better. So I have begun writing a novel…

Colin (to Clifford): Do you think there’s

any point in writing a novel anymore?

Clifford (to Colin): Not really.

Colin: I think I’ll write one.

Clifford: What about?

Colin: About us, I expect.

Conch Shell (to nobody in particular): I still can’t hear the sea.

Doctor (overhearing the conch shell’s thoughts): What can you hear?

Conch Shell: The rustle of my own calcification.

(final curtain)

Play #99: Swingin’ on the Stars

There are two characters in the play: a headstrong girl of about fourteen named Annette Cockeyne, and a certain rather starchy Miss Walpole, who is the headmistress of Ringenhall, the girls’ school Annette has been attending and which she is now in the act of leaving forever. Both characters and their first lines of dialogue are taken from the first chapter of Iris Murdoch’s second novel, The Flight from the Enchanter, published in 1956. The illustration used here is by English illustrator Edward Rawden

As the play opens, we see Annette who, having clambered up onto a massive library table and then stood on a chair she put there in order to get even higher, is now joyously swinging on a massive, cut-glass chandelier hanging from the ornate ceiling above the table. She has had two or three exhilarating swings (the cut-glass pendants in the chandelier jingling and tinkling like bells on a sleigh) when Miss Walpole ethers the room.

MISS WALPOLE (sternly): What are you doing?

ANNETTE (gleefully): Swinging from the chandelier!

MISS WALPOLE (puzzled): Why?

ANNETTE (wonder in her voice): Because the chandelier is The Milky Way. I’m out under a cold midnight sky!

MISS WALPOLE (irritably, watching Annette swing to and fro over the table)): It is just a chandelier.

ANNETTE (chagrined): Yes, of course it is. But it is also a fountain of glass upside down, showering me with its droplets. [swinging wildly] And it is the right earring of a giant, light-year princess!

MISS WALPOLE (as calmly as possible): Nonsense!

ANNETTE (with annoyingly elaborate patience): You may call it nonsense, but I call it a star-cluster, bending near the earth. It is made of my breath, now turned to shards of ice in the hard, black air!

MISS WALPOLE (terminally exasperated): You are a hateful girl! And a dangerous one!

ANNETTE (making another pass): And you are an old earthbound woman, dusty as a cobweb!

MISS WALPOLE (hurt): Annette!! You mustn’t say such things.

ANNETTE (coming slowly to a stop and carefully returning to the table below her): It’s just that you’ve never been aloft the way I was.

MISS WALPOLE: (plaintively): How could I have been? I’m headmistress!!

ANNETTE: Well do you want to trade places for a few moments?

MISS WALPOLE (tempted): I could never climb away up to the chandelier!

ANNETTE (cheerfully): I’ll help you.

[Annette helps Miss Walpole up onto the table, steadies the chair for her and shows her how to hold onto two of the chandelier’s glass pendants]

ANNETTE: Are you all set?

MISS WALPOLE (unsteadily): I guess so. Give me a push.

[Annette pushes her. Miss Walpole sweeps out over the table and, quickly cutting her fingers on the glass pendants, releases her grip on the chandelier with a shriek and falls like a sandbag against the far wall of the room. Annette rushes to her aid]

MISS WALPOLE (tearful): I couldn’t do it.

ANNETTE (sizing things up): Apparently not.

MISS WALPOLE (wrapping one of her cut hands in her handkerchief): What do you think went wrong?

ANNETTE: I think that at the very last moment, your imagination seized up.

MISS WALPOLE (tearfully): But I wanted so much to swing on your glass stars!

ANNETTE (tenderly): Perhaps you did. But not nearly enough!

(curtain)

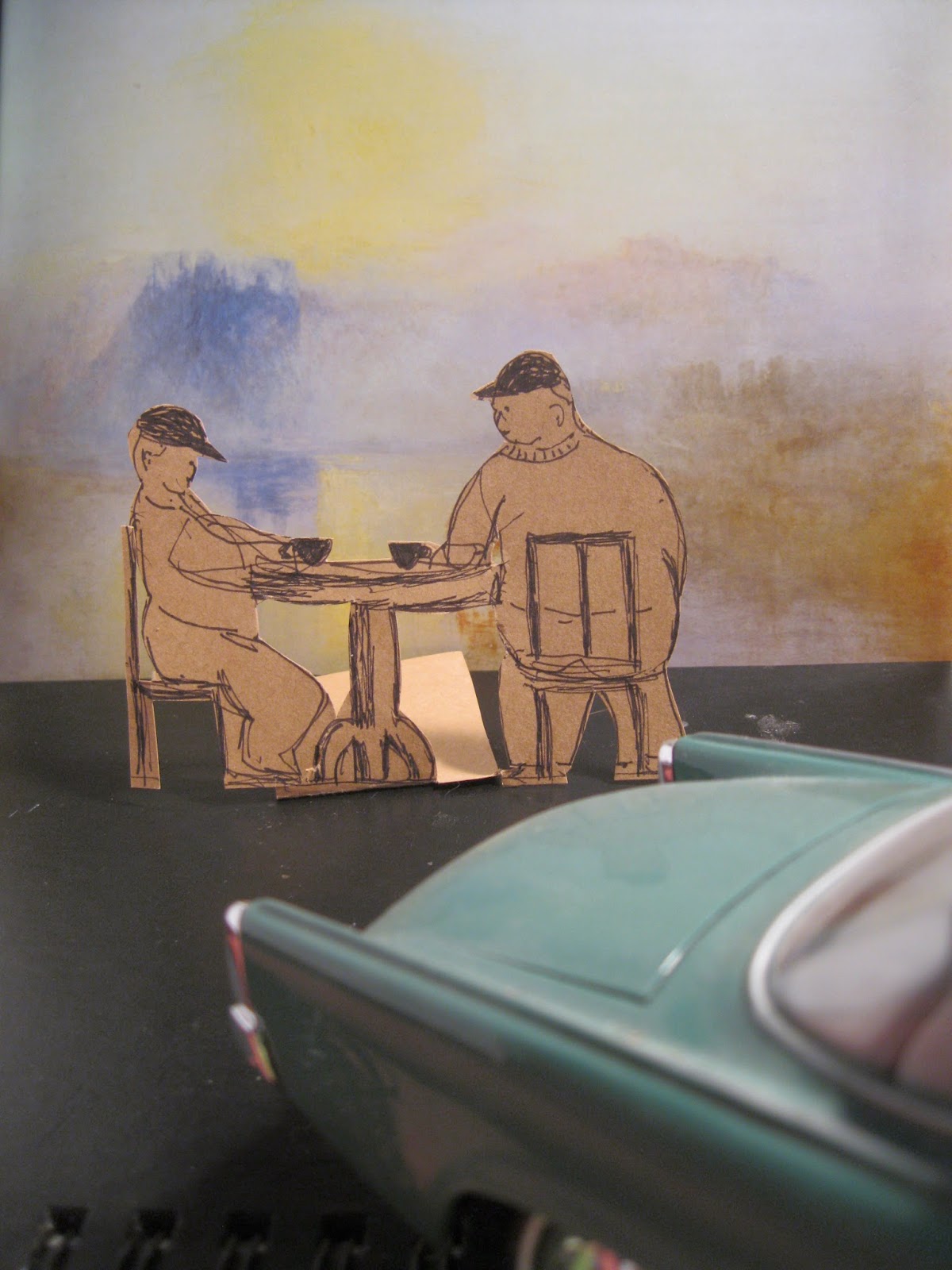

Play #98: Colin and Clifford discuss an e-Rendezvous

The play is set in The New Yorker, a small Chinese restaurant in Albany, New York. It is early on an October evening and Colin is telling Clifford about a recent e-assignation in rural Quebec.

COLIN (already exasperated): …So I get to the hotel at the appointed time and the woman hasn’t arrived.

CLIFFORD: Well, I thought you told me she had a long drive to get there.

COLIN: Even so. And then when she does show up…an hour late…I’ve already had a bite to eat at the hotel, and she then informs me that she’s hungry and wants to go out somewhere.

CLIFFORD: So what did you do?

COLIN: I took her to a steak house ten miles away and sat watching her eat.

CLIFFORD (wistfully): I like to watch a woman eat….

COLIN (irritated): Yeh? Well I don’t.

CLIFFORD (puzzled): Why not?

COLIN (with a shudder): All that elaborate mastication, punctuated with those meaningful, pleasured looks! It’s almost indecent!

CLIFFORD (sympathetic): It’s different maybe if you do it together.

COLIN: Do what together?

CLIFFORD: Eat.

COLIN (absently): Oh…yeh. And then there’s the evening to get through. And guess what? There’s no TV in the room!

CLIFFORD: So what did you do?

COLIN: I had a book with me.

CLIFFORD: What about her?

COLIN: She had her laptop, and proceeded to email everybody she knew…probably about what a schmuck she thought I was.

CLIFFORD: Why didn’t you make love to her?

COLIN (surprised and repelled): Before dark?

(curtain)

PLAY #97: Shell Game

As the curtain rises, we see two substantial Conch shells sitting side by side on a grand piano.

SHELL A: I can sense your nearness.

SHELL B: You have no eyes.

SHELL A: I have no eyes, but I am one gigantic ear.

SHELL B: What can you hear?

SHELL A: The slow crackle of your calcification—and the background murmur of the distant sea. You hear the sea too, don’t you?

SHELL A: No, I never have. I hear the vacuum cleaner and the cats chasing one another.

SHELL B: I dream of the sea all the time.

SHELL A: How do you do that?

SHELL B: I grow even more still than usual and listen.

SHELL A: Listen to what? How do you know what the sea is like? You came from a gift shop—just as I did.

SHELL B: You can’t take the sea out of a conch shell. It’s always there.

SHELL A (sadly): Not for me. I hear nothing. I think I’m just décor. Something else to dust.

SHELL B (compassionate): I’m sorry.

(curtain)

Play #96: The Doormat: A Monodrama

The play is set in a small, quiet auberge in the countryside, not far from Quebec City. It is late morning. An attractive woman of some years—she is perhaps in her early seventies—sits alone in one of the hotel’s guest suites, her laptop open on the table in front of her. As the play begins, she has paused between sentences and has opened the window that gives onto a silvered lake lying just beyond the pine trees near her room. After a moment or two, she closes the window and goes back to her typing:

Woman (typing):

Well, Mavis, he’s finally gone—back home to Albany—and I’m here in the room alone, typing this to you, looking out the window and wondering why I’m not as hungry for lunch as I’d like to be.

You are right—as usual—to point out that this little auberge is very long way from home and now that I’m still here and he’s not, it’s clearly going to be a wearisome journey back—and an anticlimactic one too. Thomas Wolfe may have decreed that “you can’t go home again” (you remember Look Homeward, Angel, don’t you, Mavis?) but sometimes you have to, whether you can or not. And I have to.

What an abyss opened up between the online man and the man himself! Between the e-man and what I may as well call the hard-copy version! And you weren’t the only one who so ringingly disapproved of this pilgrimage to my e-assignation, spending a weekend with a man I knew only through lines of beckoning typescript (Times New Roman, 18 point) inching across my little glowing screen. There was quite a bit of talk from other friends too about my head being examined. I knew of course you were all correct about this. But acknowledging the judiciousness of your friends’ advice when all you really want is to drive down an (interminable) highway and into the haven-arms of some man at the other end is pretty difficult. Impossible for me.

They say you don’t really know a person unless you’re married to him, but I say you know him quite well enough after the first five minutes you’re together.

First of all I was an hour late getting here. This generated an almost palpable surliness in my virtual lothario that never lifted! We didn’t have dinner last night because although I was starving after my long drive, he informed me that he had already eaten something on the road. We spent the evening in a sort of musty, growling silence. He flopped heavily onto the sofa and stayed there reading the auberge’s available magazines, and I stared at the wall (there is no TV in the room).

You want to know what happened later that night, don’t you dear Mavis? Dear prurient Mavis?

Well, I slept with him. Yes, in the carnal sense (when did “sleep” become a gentle euphemism for “fuck”?). You are now asking me why. I don’t know, Mavis. He clearly disliked me, and I was already loathing him. So it was scarcely a case of runaway desire! Maybe it had something to do with getting one’s money’s worth! Don’t ask me if it was any good. Of course it wasn’t. How could it have been? Performing seals, Mavis—seals!

This morning my lumpen Lochinvar awoke with but a single thought: he had to buy a doormat—with a French text on it. So we drove to a number of nearby towns, finally securing one in a Wal-Mart store. Guess what the doormat-text was? “Je me souviens.” Parfait, oui? Now, when he gets back home to bloody Albany, he can wipe his feet on the aborted romance of this blighted weekend. Je me souviens.

[she closes the laptop, looks out the window again, and sighs deeply[

(curtain)

Play #95: A Ladder Play

The play is set in a psychiatrist’s office. A middle-aged man is stretched out on the therapeutic couch, his body a veritable anthology of agonized attitudes, powered by blunted vectors of thwarted desire.

DOCTOR: Keep still!

MAN: I can’t.

DOCTOR: Where are you trying to go?

MAN: Out of my mind.

DOCTOR: Will that help?

MAN: It’s got to be better than being in here [he points irritably to his head].

DOCTOR: You need a ladder.

MAN: A ladder?

DOCTOR: Yes. [calls his nurse] Moira, will you bring in the ladder, please?

[Moira appears, struggling under the weight of a ten-foot ladder—which appears to be made of solid gold. She sets it up near the patient’s couch]

MAN: And what am I supposed to do with it?

DOCTOR: Climb it of course.

MAN (irritably): Why?

DOCTOR: Well, you don’t care much for your life down here, right? A ladder is an Ascension Machine…

MAN: What does that mean?

DOCTOR: It means that in the act of climbing it, you will rise above yourself.

MAN: That sounds alright to me.

DOCTOR: Yes, I thought it might. Well, up you go!

[The man gets up from the couch, goes to the gleaming ladder and begins to climb it]

DOCTOR (looking up at his patient who is now on the 3rd rung): How does it feel?

MAN (shouting back): It’s exhilarating!

DOCTOR: Just as I told you. [there is a pause] Okay, you’d better come back down now.

MAN (exuberantly): Not on your life! I like it up here! And l’m going all the way…

[and as the doctor and Moira watch, the man ascends the ladder, rung by rung, until he disappears entirely from view]

DOCTOR (to Moira): What’s my next appointment?

MOIRA: You don’t have one, Doctor. You’re free.

(curtain)

Play #94: The Endless Woozle

The Play is set in the Seven Acre wood, home to both Winnie-the-Pooh and his friend Piglet. On this particular day, a blustery day in winter, Piglet has set out on a snowy walk and comes upon his friend Pooh wholly engaged in a kind of project.

PIGLET: Hallo Pooh! What are you doing?

POOH: I’m, hunting.

PIGLET: Hunting what?

POOH (mysteriously): Tracking something.

PIGLET (coming closer): Tracking what?

POOH: That's just what I keep asking myself. What? I won’t really know until I catch up with it.

PIGLET: I suppose not.

POOH (excitedly): But look there. [He points to the snowy ground in front of him]. What do you see there?

PIGLET (sagely): Tracks. Paw-marks.

POOH (equally sagely): Yes.

PIGLET (excitedly): Oh, Pooh! Do you think it's a--a--a Woozle?

POOH (considering this): It may be. Sometimes it is, and sometimes it isn't. You never can tell with paw-marks.

[Pooh now comes to a sudden stop, and bends over the tracks in a puzzled sort of way]

PIGLET: What's the matter?

POOH: It’s very funny thing, Piglet, but there seem to be two animals now. This--whatever-it-was--has been joined by another--whatever-it-is.

[Suddenly Winnie-the-Pooh stops, and points excitedly in front of him]

POOH: Look!"

PIGLET (frightened): What?!!"

POOH: The tracks! A third animal has joined the other two!

PIGLET (nervously): Another Woozle, do you think?

POOH (in a somewhat Sherlockian manner): No, Piglet, because it makes different marks. It is either Two Woozles and one, as it might be, Wizzle, or Two, as it might be, Wizzles and one, if so it is, Woozle. Let us continue to follow them.

[And so Pooh and piglet go on following the Woozles or Wizzles until they are following four different tracks and then ten different tracks and—as the light begins to fail—fourteen sets of tracks and then, an hour later, twenty-eight. They begin to grow very weary indeed of tracking, hut they keep tramping on, round and round and round.

POOH (sitting on a snowy bough to one side of the path): I’m tired. I need a rest, Piglet.

PIGLET: So do I.

[after a short break, they get up and begin their tracking again]

POOH (surprised): We now appear to be following sixty-eight different Woozles!

PIGLET: Or one Woozle and sixty-six different Wizzles!

[they make another circle in the snow]

PIGLET (looking down at the tracks in the snow): And now there are seventy of them!

POOH (surprised at the way Woozles mount up): Imagine!

PIGLET (imploringly): Let’s go home, Pooh.

POOH: Well, it is way past our suppertime!

PIGLET: We’ll start again tomorrow, Pooh.

POOH: Yes.

(curtain)

Play #93: Orion

The play is set in Berlin in June of 1933. Playwright Bertolt Brecht is getting ready to leave Germany for the safety of Denmark. Before he goes, he must placate or otherwise listen to the forlorn demands for affection and loyalty addressed to him by the various women in his circle—Elisabeth Hauptmann, Ruth Berlau and others—most of whom, except for his wife, Helene Weigel, were both lovers and, if you do the research, unacknowledged collaborators in the writing and staging of his plays.

As the play opens, Brecht is talking with distraught actress and writer Margarete Steffin (1908-1941)—who appears to have contributed a good deal to Brecht’s Galileo and to his The Good Woman of Setzuan. Steffin is already suffering from the tuberculosis that will kill her eight years hence. Brecht tells the unhappy Steffin that he would cheerfully divorce Helene Weigel and marry her—if only she were not ill (though he has pointedly refused all along to give her money that would help to secure her the treatment she needs—and never gets!).

[Note: What follows is derived from a single page—page 299—of John Fuegi’s still controversial Brecht & Co.: Sex, Politics, and The Making of Modern Drama (New York: Grove Press, 1994)]

STEFFIN: Why don’t you understand? I need to have something of yours while you’re gone! Some part of you to be here with me!

BRECHT (reaching into his pocket): I’m going to give you a ring. [he places three cheap metal rings on the table between them].

STEFFIN (crestfallen): There are three identical rings here. Who are the other two for?

BRECHT (irritated): What does it matter? Choose one for yourself.

STEFFIN (picking a ring, almost at random): Thank you.

BRECHT (with ersatz heartiness): There’s more.

STEFFIN (weary): Yes?

BRECHT: Yes, a second gift—this one from heaven!

STEFFIN (depleted): I don’t understand.

BRECHT: Look up at the night sky.

STEFFIN (she glances up): Yes. And so?

BRECHT (patiently): The constellation you see wheeling above us is Orion—the great hunter.

STEFFIN: Yes? But I don’t understand what you are showing me. You spoke of a heavenly gift?

BRECHT (triumphantly): This is it! From now on, while I am away, we can both look up at Orion—from wherever we are—and be joined in the heavens!!

[Steffin buries her head in her hands and weeps]

(curtain)

Play #92: Colin and Clifford, on the Road.

Colin and Clifford are traveling. It is the end of summer and, as the two of them sit with cups of coffee before the splendour of a roaring sunset, they begin to talk about where they’re going.

COLIN: Maybe we should push on if we want to make Tobermory before nightfall.

CLIFFORD (abstractly): I guess:

COLIN: Lots of wrecks in Tobemory.

CLIFFORD (distractedly): Glad to hear it. They’re going to love us.

COLIN: No, I meant ship wrecks. You know, under the water.

CLIFFORD: Carelessness.

COLIN: I’m sure none of them were deliberate. You know how things can go wrong.

CLIFFORD: Maybe the chamber of commerce put them there—to give the skuba divers something to find.

COLIN (wearily): Jeez, Clifford, Coffee makes you so goddam cynical!

CLIFFORD (grinning): I lean back on it.

COLIN (looking up at the incendiary sky): Some sunset, huh?

CLIFFORD (agreeing): Big.

COLIN: Yeh. Makes you feel small.

CLIFFORD: Maybe it makes you feel small. It makes me hungry.

COLIN: Okay, so we’ll go eat.

CLIFFORD (draining his cup): Right.

[a lengthy pause]

COLIN: Listen do you ever think about what happens when you die?

CLIFFORD: Never. And especially not when I’m hungry.

COLIN: Okay, well try to think of it now. I’m asking you again. What are you planning go do when you die?

CLIFFORD (off the top of his head): I thought I’d just lie on my back and look at the stars…

COLIN: But things…well, you know…there are likely to be transformations. Declensions. A dwindling of some kind.

CLIFFORD (with great finality): I’m going to lie on my back and look at the stars…until we get all mixed up together.

(curtain)

Play #91: The Wild Ass’s Waistcoat (after Balzac’s The Wild Ass’s Skin, 1831)

The play is set in the present, at the heart of any contemporary city. Its protagonist, Raphael de Valentin, is a struggling but penniless young writer and aesthete who, having failed at everything, has made one final visit to an antiques store he likes (even murderous depression cannot really staunch or quell a genuine lust for objects of virtu) before going back to his rented room kill himself.

Although Raphael has no money with which to purchase anything, the demonic antiques dealer nevertheless offers him something gratis: an exquisite vest made from an untanned wild ass’s skin. Raphael, naturally suspicious, is not so suspicious as to resist the idea that this peculiar vest might not add a touch of glamour to his otherwise sordid demise-to-come.

Raphael: Well, I scarcely know what to say.

Dealer (heartily): Yes, it’s a remarkable garment. The skin from which it is made is very old—they say it goes back to the days of King Solomon!

Raphael: It’s exquisite.

Dealer: Yes, well, wear it in good health, my boy!

[Alas for the hapless Raphael, he knows nothing of the vest’s strange and sinister secret—to whit: because the vest is a) untanned and b) magical, it offers its wearer the fulfilment of three wishes. The trouble is that with every wish the garment grants, it also shrinks substantially, each shrinking representing a shortening of the wearer’s natural life by fifteen years. If Raphael really were about to commit suicide, this might not matter, but when he discovers the vest’s enchanted generosity, suicide doesn’t seem nearly as attractive as it did before. So instead of killing himself, Raphael immediately gets rich. So far, he had made two wishes and, with the two wishes in aggregate, he moves closer and closer to death. When w see him next—rich and swell-satisfied, if a little snug about the waist—he has one wish left].

Raphael (driving his new yellow Hummer across the city with his girl de jour cosily nestled seven or eight feet from him on the Hummer’s front seat): O where will it all end?

(curtain)

Play #90: The Utopian Turtletopper

The play is set in poet Marianne Moore’s apartment in Brooklyn. It is the autumn of 1955. As the play opens, Moore is talking with Robert. B. Young, of the Marketing Research Department of the Ford Motor Company. Ford is trying to come up with a sprightly new model and, to that end, have come to ask the famous poet if she can possibly suggest a compelling name for the new car. They have helpfully provided a big photo of the embryonic vehicle, which Mr. Young has just taped to the wall of Moore’s apartment.

Moore: That’s it?

Young (proudly): That’s it. Can you help us with a name? Another Thunderbird would be fine!

Moore: Yes, I liked Thunderbird too. Well, how about The Ford Silver Sword?

Young (embarrassed): Well, I….uh….

Moore (continuing): Or The Resilient Bullet.

Young (more embarrassed): Oh I don’t think….no.

Moore (with mounting enthusiasm): The Ford Faberge!

The Mongoose Civique. The Aeroterre!

Young (weakly): Well, I guess Aeroterre isn’t too bad….

Moore (exuberantly): I’ve got it!”

Young (expectant): Yes?

Moore (triumphant): The Pastelogram!!

Young (defeated): That’s ridiculous.

Moore (still perky): Is it? Okay, here’s my very best suggestion yet.

Young (beyond caring): Great.

Moore (with barely suppressible delight): Utopian Turtletop!!

[Young buries his head in his hands]

Moore (tenderly): I see you like that one too!

(curtain)

Play #89: The Carcass of Beef

The play takes place in the threadbare Paris studio of Russian immigrant painter, Chaim Soutine, at 14 Cite Falguiere, near the Boulevard Montparnasse. It is the summer of 1922, and Soutine, desperately poor, spectacularly unkempt, grievously undernourished and aesthetically obsessed, is making a painting of an entire side of beef which, bloody and dripping, he has strung up in his studio before his waiting easel. On the morning of the play, Soutine has received a visit from his best friend, painter Amedeo Modigliani—who is every bit as hungry and as needful as Soutine is.

Modigliani (watching Soutine paint): A side of beef is pretty expensive, isn’t it?

Soutine (wearily): Fantastically. I took me months to save up enough money to pay the butcher.

Modi (gently): You could have bought food for yourself.

Soutine (pointing proudly to his almost finished canvas): This is more nourishing for me!

Modi: The carcass stinks something awful!

Soutine (calmly): Well, I work very slowly. The thing started to decay about a week after I hung it up. It’s been there a month. But isn’t it glorious?!

Modi: Chaim, the whole neighbourhood reeks of it.

Soutine (more calmly still): Well, I’m almost finished.

Modi: When will it be done?

Soutine: Today. Tomorrow. Next week. Will you help me get rid of the carcass when I’m through? It’s too big to just throw in a dustbin.

Modi: (laughing): I suppose I’ll have to, just to freshen the air. Where will we take it?

Soutine: I don’t know. Out. Away.

Modi: Away?

Soutine: Away from here.

Modi: A long way from here!!!

(curtain)

Play #88: The Optical Tiresias or Gendered Vision

The play is set in the office of ophthalmologist, Dr. U. Will Seewell , who has recently performed a cornea transplant upon his patient, Ichabod. C. Fine.

Dr. Seewell: Now tell me, Ichabod, how is your vision since the transplant?

Ichabod: Okay I guess. About the same as before.

Dr. Seewell: But no better?

Ichabod: Not really.

Dr. Seewell: But no worse, surely?

Ichabod: No. I do have a question, though.

Dr. Seewell: Of course

Ichabod: The replacement cornea you gave me—was it from a male donor or a female one?

Dr. Seewell (looking through Ichabod’s file): Female, I believe [checks again]. Yes, female.

Ichabod: I see.

Dr. Seewell: Why do you ask? After all, a cornea is a cornea.

Ichabod: But is it really true? I mean nothing else about a woman is anything like a man. Apart from the obvious reproductive differences, look at a woman’s hands. Her feet. Her nose. Her cheekbones. Her ankles. Throat. Back. Hair. Shoulders. Her wrists…

Dr. Seewell (quietly): And her eyes.

Ichabod: Yes.

Dr. Seewell: Why exactly do you care?

Ichabod: Well, I was just thinking about how, if I close my left eye, I now see the world only through a woman’s cornea. And if I close my right eye, I see everything with my own cornea the way I used to—a man’s view of things.

Dr. Seewell: I never thought of it that way. So can you detect any real differences between what you see with each eye?

Ichabod: Not that I’ve noticed so far.

Dr. Seewell (amiably): So you’re suspending judgement for a while?

Ichabod (chuckling): I’m keeping both my eyes open!

Dr. Seewell (smiling): Blended vision!

Ichabod (smiling back): I’m an equal-opportunity seer!

(curtain)

Play #87—With Colin and Clifford at the Active Volcano Café

The play is set in a small cafe in a quiet town in Eastern Ontario. The cafe, which was once known as The Downtowner, has recently been redecorated by the owner, and has now been reborn as the Active Volcano Café—no doubt because of the presence on the back wall of an enormous mural depicting, albeit crudely, two black-and-white volcanoes out of which furl billowing clouds of thick black smoke. The new volcanoes dominate everything—even conversation.

Colin: What are you going to have? A latte?

Clifford (vaguely): Sure, I guess.

Colin: You seem a bit abstracted.

Clifford: Insufficiently present, right?

Colin: Yeh.

Clifford: It’s these damned volcanoes.

Colin: Well, they are sort of aggressive.

Clifford (darkly): Sinewy black smoke rising.

Colin: Muscular.

Clifford (still more darkly): Rising from big volcano shoulders.

Colin: Why are they here, do you think?

Clifford (suspiciously): Maybe they’re not.

Colin: They’re just a projection, you mean?

Clifford: Well, it happens.

Colin: But here? At the Downtowner?

Clifford: That‘s all different now, remember? It’s the Active Volcano Café now.

(curtain)

Play #86: Helpless

"I know one thing: that I know nothing"—Socrates

The play takes place at seven o’clock on a weekday morning in the second floor bathroom of a comfortable, middle-class house on a shady street in small town in Eastern Ontario. A middle-aged man, Albert Curtius, is brushing his teeth. He suddenly stops, looks down at his toothbrush and his toothpaste, and calls out to his wife, Abigail.

Albert: Abigail!

Abigail (poking her head into the bathroom): Yes, Albert?

Albert (puzzled): What is tea-tree oil toothpaste?

Abigail (patiently): Toothpaste made from tea-tree oil.

Albert (impatient): Yes, but what is a tea-tree? Where do they grow? How do you make toothpaste out if it? Why is the oil so desirable?

Abigail (calmly): It’s good for us, dear.

Albert (still impatient): Is it? But why, Abigail? How?

Abigail: I don’t know.

Albert: I don’t know either. And as a matter of fact I’m suddenly discovering that I don’t really know much about anything at all! It gives me a strange, lonely feeling.

Abigail (soothingly): You’re tired, Albert. The feeling will pass.

Albert (a note of panic developing in his voice): But it doesn’t. In fact it’s getting worse all the time! Think about the water I’ve been using to brush my teeth. What is it?

Abigail (perplexed): What is water?

Albert (impatient): Well, okay, yes, it’s apparently two gasses mixed together, yes. Hydrogen and Oxygen, sure. But how? Can we make it ourselves? No. Where does it come from? This faucet? The lake? The clouds? The sky? The Polar Ice Cap? It pours out of this faucet. And by the way, what is this faucet made of? Steel? Chrome? Chrome-plated steel? What is Chrome?

Abigail: The shiny stuff on cars?

Albert (relentless): Maybe. Is that stuff chrome? I was just looking at shiny finish on this fixture. Is it a metal or just a coating? What is it made of? And what about this sink the water falls into? Is it porcelain? Or some kind of ceramic? What is porcelain? The name makes it sound delicate and expensive. But what is it? Is it different from China? If so, how? Maybe it’s just made of plastic. But why do I say “just” plastic? Why do we tend to look down on plastic? How is plastic made, and what part does petroleum play in making it? Some commercial soft ice cream is made with “edible petroleum products.” What are those products? Does this mean that a soft ice cream cone is made of plastic? Why is some plastic called “space-age plastic? Is it different from the plastic they make drinking glasses and sunglasses out of? What was Bakelite? Early plastic, right? Do they still make it? The steering wheel of my uncle’s 1948 Buick was made of Bakelite. Why was Bakelite soft and sort of slippery—like jade? What is jade for that matter?

Abigail (soothingly): Go and lie down for a bit, Albert.

Albert (agitated): Where? On our bed? The blankets are made of wool, right?

Abigail: some of them.

Albert (growing panicky): Why do sheep grow wool?

Abigail (calmly): To provide blankets, Albert.

Albert: Are you sure? I thought it was to feed their young.

Abigail: Lambs don’t eat wool, Albert.

Albert (triumphantly): But moths do! I see them doing it! But moths don’t eat the wool from real sheep. So how do they know to wait until the wool is made into blankets?

Abigail (imploring him): Please, Albert, lie down and take a little rest!

Albert (beside himself): Take it where? Why do you say to take a little rest? Why not “have” a rest, “embark” on a rest?? Where am I going to take it to? It sounds like medication—take an aspirin!

Abigail (leaving the room): Not a bad idea either!

(curtain)

Play #85: The Homily

Over at Miss Lilys café in Picton, Ontario, just exactly beside the table where, on this sunny Spring morning, Magorzata and I are drinking coffee and eating apple turnovers, there is a shelf on which rest a number of irritatingly chatty, downright loquacious china cups, each of them stuffed with a complimentary bag of fancy-dancy tea—as an incentive to purchase them.

The longer I stare at these cups—and they really do seem to stare back at me—the more irritating their bromidic messages become (and curiously, it seems impossible not to read them aloud). One of the cups is particularly annoying. It reads (the text is swathed about with ghastly childlike flowers): Only Do What Your Heart Tells You.

GMD (holding the cup up so Malgorzata can see it, thus wrenching her away from her browsing through Marguerite Yourcenar’s The Abyss, which we have just bought for a dollar on a sale table in the bookstore adjoining the cafe): Look at what this cup says.

M (dutifully peering at it): Strange advice!

GMD: Isn’t it? [reads the cup aloud] Only do what your heart tells you.

M (yearning to return to Yourcenar): Dangerous.

GMD: I think so too.

M: And grammatically inelegant. Don’t they mean “Do ONLY what your heart tells you? Not “only do”?

GMD: I think they probably do.

M: “What Your Heart Tells You” is pretty open.

GMD: It’s like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, talking about finding “her heart’s desire” right in her own backyard—no matter what it turns out to be.

M: Backyard desire. Sounds a bit limited.

GMD: Could be an early play by Eugene O’Neill!

M: What would you do if you took the cup’s advice?

GMD: I think this cup is an evil, anarchic cup at heart. I think it would prompt me to buy it, take it outside and hurl it back at the front window, breaking it into a million pieces! I could blame it all on the cup!

M (smiling gaily): I hope the cup knows a good lawyer!

(curtain)

Play # 83: The Right Hand

Fashion photographer Randy Medici is on a quest to discover—and employ—the perfect female hand. He needs it so that he can start making the photographs for the upscale designer-bracelet campaign he just beginning for Harper’s Bazaar. As the play opens, his New York studio is abuzz with a dizzying array of models—all of whom have hands to offer for his consideration.

Randy (impatient, harried): Just the right hand, sweetheart. Just hold it up.

Girl 1 (holding up a hand): Is this my right, Randy?

Randy (gently): Yes it is, Kate. But it’s quite the wrong sort of hand, I’m afraid.

Girl 1: It is?

Randy: Yes. It’s too white, too moon-pale, dear. Too medieval! I need something more vigorous. The sort of hand you’d find at the end of a tennis racket! Next!

Girl 2 (holding up her hand and waving it): Hi Randy!

Randy: Hold it still, sweetheart.

Girl 2: It’s a lovely hand, don’t you think, Randy?

Randy: Yes I do—but it’s a period hand. Way too 1950s!

Girl 2 (puzzled): What do you mean?

Randy: It’s a very nice hand, Heather, but it’s a Jayne Mansfield hand! It’s all balloon tires and whitewalls, sweetheart! It’s a tailfin hand! What I need, you see, is more of a Breakfast-at-Tiffany’s hand?

[The girls continue to parade by, holding out their right hands—a pageant that goes on for the next hour and a half]

Randy: Sorry sweetheart, too bony.

[Another hand is offered]

Randy (impatient): No no NO! That’s a bloody Regency hand. Right out of Jane bloody Austen!

[And another]

Randy (growing weary): Too Venetian. Too Grand Canal!

[And still another]

Randy (exhausted): Mannish.

[And one more. It will be the last hand of the morning. Its donor is swathed in yards and yards of black silk crepe de chine, from which is tentatively extended a small, porcelain-like hand that shines under the studio lights like the phosphorescent belly of a fish on a bed of cracked ice.

Randy (breathless, the old excitement stirring again): What kind of a hand is this?!! This perfect fruit! This greengage plum of a hand! This worldly-wise embryo of a hand!

[The black-swaddled donor says nothing. The air in the studio has stopped moving and is mica-hard. Randy can scarcely breathe. A couple of the models faint.

Violently agitated and yet desperate to understand, Randy moves towards the mysterious figure and, reaching out, plucks the black veils of crepe-de-chine away. What is underneath, balancing on wooden, stilt-like, prosthesis-legs strapped to her calves, is a dainty child of about six—a little girl, white-faced and staring]:

Prosthesis-Child (holding up her diminutive hand ever higher towards Randy): This is my hand.

Randy (transfixed): It’s exquisite.

Prothesis-Child (quietly): I have another as well.

Randy (more or less unhinged): Do you?

Prothesis-Child: My mother told me to come here and offer this one to you. She said you would like it.

Randy: Did she?

Prothesis-Child (wonderingly): She did. I don’t know why she said that. It’s just my hand.

Randy (now thoroughly enchanted): Yes. So it is.

(curtain)

Play #82: The Blue Wheel

The play is set in the desert near Harar, Ethiopia, in August of 1884. Rimbaud, his poetry now definitively behind him, is working in the coffee trade, overseeing the export of the coffee of Harar to Europe. When the play opens, Rimbaud and his friend, Alfred Ilg, a Swiss engineer, are taking a morning walk together. It is only just after dawn, but the sun is already merciless.

Ilg: How did you come to the coffee trade?

Rimbaud: Harar coffee is the best in the world.

Ilg: No question, but why did it need you?

Rimbaud: I suppose I found selling coffee to be a slightly less empty occupation than selling guns.

Ilg (risking everything): Tell me, Arthur, is Abyssinia one of your “Floridas incredible”?

Rimbaud (as if he has just been slapped): What?

Ilg (persevering): “I've slammed myself / into Floridas incredible / mixing petals / with panther / eyes and human skin / while under oceanic skies / rainbows reined / the sea-green herds."

Rinbaud (revolted). Bah! What’s that, The Drunken Boat?

Ilg (quietly): You know it is.

Rimbaud (angrily): Well, keep it out of the desert. There can be no boats here, drunken or otherwise!

Ilg: But don’t you miss poetry?

Rimbaud: I don’t think of it—unless some well-meaning fool like you rubs my nose in it!

Ilg: I don’t think you’re very well, Arthur.

Rimbaud (exasperated): Oh, who is, Alfred?

Ilg (glancing down at his friend’s legs): Your knee seems to be giving you some trouble.

Rimbaud (annoyed): Everything gives me some trouble.

Ilg: You need rest.

Rimbaud (confidentially): You know what makes it better sometimes?

Ilg: What?

Rimbaud: I imagine I am a big blue wheel—a big spoked wheel, like the front wheel of some giant bicycle….

Ilg: Taking the weight off…

Rimbaud: Rolling over the burning sands.

Ilg (hopeful): That’s a poem, isn’t it?

Rimbaud: No. That’s a wish. Poems come unbidden...whereas I really long for the blue wheel!!

(curtain)

Play #81—Fuseli Paints The Nightmare

The play is set in the London studio of painter Henry Fuseli. It is March of 1781, and he is preparing to paint what will come to be seen as his masterpiece—The Nightmare.

As the curtain rises, Fuseli is interviewing a young woman who may well serve as the model for what will eventually be the bedevilled, dreaming woman in the painting. The prospective model’s name is Ivy Underling.

Fuseli: How old are you, Miss Underling?

Ivy: Seventeen, sir.

Fuseli (surprised): Is that all? I took you for more.

Ivy (smiling wanly): It’s the deprivation, sir.

Fuseli (Uncertain he heard properly): The deprivation?

Ivy (a bit flustered): Oh you know, sir. Doing without and all that. It makes you old pretty quick.

Fuseli: Oh. Yes, I suppose it could.

Ivy (her voice tremulous): What would I have to do if I model for you, sir?

Fuseli (expansive): My dear young woman, it is simplicity itself! First, you’ll be stretched out full-length on a divan—on your back.

Ivy (alarmed): I won’t be in me altogether, will I sir? I couldn’t do that!

Fuseli (momentarily confused): Your altogether? Oh, you mean naked! No, no, of course not.

Ivy (smiling): That’s a relief then!

Fuseli (abstractly): Yes. Yes. But you will have to put up with a rather large monkey sitting on your chest!

Ivy (horrified): A monkey? A real one?

Fuseli (irritated): Yes of course a real one. Where am I going to get a stuffed monkey that big?

Ivy (tremulous): Will it be a tame one?

Fuseli (patiently): Oh yes, it has to be. Because I have to tie a twisted, grinning mask to its face.

Ivy (suspicious): Just what kind of a painting is this going to be anyhow?

Fuseli (offhand): A work of considerable genius, I imagine.

Ivy (shaken but curious): Does it have a title?

Fuseli (cheerfully): I’m calling it The Nightmare.

Ivy (getting interested): Because of the monkey with the evil face??

Fuseli (casually): That, and because of the screaming horse with big popping white, sightless eyes that has thrust its hideous head through the curtains to stare at you while you are sleeping!!

Ivy (finally getting used to this): A real horse?

Fuseli (annoyed): A real horse with white eyes as big as croquet balls??!! Where would I find such an animal? No, I expect I shall have to make him up!! The monkey too, perhaps.

Ivy (picking up her cloak and slipping it on): In that case, Mr. Fuseli, I think you’ll have very little difficulty making me up too!! Now I’ll take my leave.

Fuseli (incredulous): And miss your chance at immortality??

Ivy (putting on her bonnet): If need be, sir, yes. I suspect immortality just isn’t for me. Good day to you, Sir!

[she leaves the studio]

Fuseli (watching her leave): Young people today! Who can understand them?

(curtain)

Play #80: Cow in the Road

The play is set in a courtroom. There is a closed hearing in progress. The venerable judge, one Milton Pepperleigh, sits up at his lofty seat of judgement. Before the bench stand two vigorous lawyers: Timothy Millstone, who represents the plaintive, a farmer named Abner Apple, and Harry Wanderlust, who represents the defendant, a used car salesman named Shark Sturgeon.

The case, in a nutshell, is this: Abner Apple, the farmer, was driving his cow, Evelina, along a short length of highway, making sure that the cow—which was untethered —was all the while keeping to the gulley along the side of the road, where both cow and farmer were walking (with the cow in front). Salesman Shark Sturgeon was driving south on the highway at the same time as Abner was escorting his cow (presumably to a nearby pasture).

For reasons we shall now never discover, Evelina—who knew this terrain well—suddenly decided to cross the highway to the field on the other side. Abner was unable to restrain her. In the midst of crossing the road, the cow was struck by Stark Sturgeon’s car and killed.

Abner Apple is suing Stark Sturgeon for damages. He says Evelina was worth $400, and he wants $400.00 to compensate him for his loss. Stark Sturgeon’s counter- argument accuses farmer Apple of negligence in allowing Evelina to walk along untethered and to be, therefore, out of his control. He insists that the cow strode so suddenly into the middle of the road there was no way he could bring his speeding car to a stop before running into the animal. He adds, moreover, that the damage to his car was even more than the $400 demanded by Farmer Apple.

Timothy Millstone (acting for Abner Apple): …and we say that Mr. Sturgeon was driving his car far too fast and was therefore unable to stop for….uh…

Abner: Evelina.

Millstone: Yes, Evelina.

Harry Wanderlust (acting for Shark Sturgeon): It has been already established that my client, Mr. Sturgeon, was driving at exactly the proscribed speed limit. The trouble arose because Evelina’s owner, Abner Apple, had allowed the cow to walk beside the highway untethered.

Abner (chuckling): Evelina was a free-range cow!

Judge Pepperleigh (sternly): Let me remind you, Mr. Apple, that I am the only one allowed to make jokes here.

Abner (contrite): Sorry, your honour.

Millstone: It was Mr. Sturgeon’s responsibility to bring his vehicle to a safe stop.

Wanderlust: Nonsense! The cow bolted out in front of him—l like a deer!

Abner (sadly): Evelina couldn’t bolt. She was too old to bolt!

Millstone: The cow was walking so slowly that Mr. Sturgeon had plenty of time to see her and avoid her! IF he was watching the road at all!! Which we doubt.

Wanderlust (with finality): He was indeed watching the road.

Judge Pepperleigh (judiciously): At the basis of this case is a curious situation in which mechanism—in this instance, Mr. Sturgeon’s car—has come into curious, abrupt confrontation with the pastoral mode—in this instance, Evelina, Mr. Apple’s cow. It is clear to me, that what lies at the heart of the matter is our reading of the concept of Responsibility. Who—or what—is responsible for Evelina’s demise? I’m now calling a short recession until I give some further thought to this troubling matter of “responsibility.”

[He goes to his chambers. Four hours pass, in agonizing slowness. Then Judge Pepperleigh returns. He assumes the bench, cleans and adjusts his spectacles, puts them on peers down at Millstone and Wanderlust]

Judge Pepperleigh (weighing every word): Gentlemen, there are hierarchies of irresponsibility in this case. Yes, Mr. Sturgeon ought to have been paying closer attention to the road ahead. Yes, Mr. Apple ought not to have allowed Evelina to trot along untethered. And yes, Evelina—who should have known better—ought not to have bolted across the highway, making for the other side. Clearly, of all the three parties, Evelina herself acted the most irresponsibly, and if she were here, I would unhesitatingly tag her as the Guilty Party. But she is not. All I have to say to all of you gentlemen, therefore, is this: There is no worse place to be than the Middle of the Road!

This hearing is now dismissed.

(curtain)

Play # 79: Preordained

Note: The play is based on a discussion in Chapter XVIII of My Autobiography by Charles Chaplin (London: The Bodley Head, 1964) where Chaplin muses that “there are philosophers who postulate that all is matter in some form of action, and that in all existence nothing can be added or taken away. If matter is action, it must be governed by the laws of cause and effect. If I accept this, then every action is preordained. If so, is not the scratching of my nose predestined as much as a shooting star? The cat walks round the house, the leaf falls from the tree, the child stumbles. Are these not actions traceable back into infinity? We know the immediate cause of the fallen leaf, the child stumbling, but we cannot trace its beginning or its end” (p.313).

The curtains open to reveal a comfortable living room, in which, on a large flowered sofa, sit a middle-aged couple. They are both in a ruminative mood, and both are carefully watching everything that takes place before them—as if they were onstage.

[The man suddenly scratches his nose]:

The Woman: You see?

The Man: What?

The Woman: That’s an antique act…an ancient event!

The Man: What is?

The Woman: Your scratching your nose.

The Man: How do you mean?

The Woman: Well, it’s as if you’ve really been doing it forever. Scratching your nose forever. To infinity— backwards and forwards.

The Man (slightly defensive): Just like your sitting there on the couch.

The Woman (looking down): What?

The Man: Your sitting there on the couch—but for ever, for always!

The Woman (determined to be rational): I’ve only been here for a few minutes!

The Man: Well, it’s no different than my scratching my nose.

[A cat walks through the room]

The Man: And now a cat walks through the room!

The Woman: Just as it always has, is that what you’re going to say?

The Man: Well, it’s another action.

The Woman (also feeling defensive): So is your next breath!

The Man: Yes. Exactly! And because these are actions, they are all preordained.

The Woman (irritated): So the cat’s not making much progress.

The Man (with satisfaction): Nor is anything else.

[Suddenly, a leaf falls from somewhere above them, gently landing on the carpet]

The Woman (enchanted): The leaf!

The Man: I saw one fall yesterday as well.

The Woman: Oh that was the same leaf. It falls everyday at precisely this time. It always has.

The Man (amazed): And always will?

The Woman: Oh yes, always always always.

(curtain)

Play #78: The Loneliness of the Long Distance Painter

The play is set in an artist’s studio. There is an enormous painting—a rough, wild, unfinished one—stapled to one wall. A small wooden chair sits facing it—about fifteen feet from the work-in-progress.

This is a one character play, a monologue by the painter.

He enters the formerly dark studio, switches on the lights, lowers himself heavily into the chair, takes a vigorous pull of the drink he has brought with him and settles down to gaze upon the painting.

Painter: My god it’s as big as the sea! It’s bigger when you sit down and look at it than it is when you‘re up close to it with a brush.

It rears up at me…like a wild horse

It’s like an ocean liner bearing down hard upon a fishing boat in its path

Can I get out of its way, I wonder?

Only by finishing it, I suppose

That’s me [he laughs raucously] The fishing boat. Poor fishing boat, trying to get a fish on the line.

A big fish. A whale. Moby Dick.

Call me Ahab, goddammit, not Ishmael!

[silence]

I wish Lucinda could see it. No, actually I don’t. Screw it. She’d have useful things to say about it. Procedural things, well-considered…

[he takes another gulp of his drink]

And I don’t want that. For me, the thing is like a Forest Fire. I don’t wish to discuss its bloody deportment!

[There is a long silence]

Christ It’s cold

And quiet. I could put some music on

But then I couldn’t hear the painting.

I couldn’t hear its clamour. All those angel voices woven together

It makes a noise

like ripping cloth

(curtain)

Play #77: STANDARD TIME

The play is set in a coffee shop in a small town in Eastern Ontario. Two burley men—Clifton and Henry—sit at the counter, finishing their coffees.

Clifton (looking at his wristwatch): What time is it?

Henry (clearly bored with Clifton): Why?

Clifton (glancing out to the street): They’re supposed to be picking me up.

Henry (bored): Who?

Clifton (anxious, but trying to sound offhand): The others.

Henry (absently): Well, if they said they’d pick you up, then they will.

Clifton: I better phone.

Henry (exasperated): No, you don’t have to phone. They’ll be here.

Clifton (seeking comfort): How do you know?

Henry (bored again): Well, you said they always pick you up, don’t they?

Clifton (nervously): What time is it now?

Henry (curtly): Same as it was before.

Clifton (perturbed): It couldn’t be!

Henry: Well, pretty close to it.

Clifton (looking around anxiously): I gotta find somebody else to ask!

Henry (growing tired of it all): Why?

Clifton: To see what time they have.

Henry (angry): You always do that!! You ask me the time and I tell you and then you don’t believe it!

Clifton (calmly): I believe it. I just don’t trust it.

Henry: Trust it?

Clifton: Well, it’s always different. How can you trust that? How can you trust any one time?

Henry: Well, there’s always standard time. You could trust that.

Clifton (despairingly): But where do you find it? You can never find it!

Henry (with finality): It’s an act of faith, Clifton. You have to trust all that Absolute stuff!!

(curtain)

Play #76—We Used to Spin Like Tops

Two older children are sitting stiffly in chairs, placed opposite to one another, in their parents’ living room. The girl, Helen, is thirteen years old. Her brother, Mark, is fifteen. They sit for a long while in silence until, finally, Helen speaks:

[Note: Helen’s first speech is taken directly from Helene Cixous, Insister of Jacques Derrida (Stanford University Press, 2007, p. 23]

Helen (tentatively): Do you remember when we used to spin like tops?

Mark (enthusiastically): Bounce like rubber balls!

Helen (excited): We Leapt like kites!

Mark (equally excited): Floated like feathers!

[There is a lengthy pause]

Helen: But of course that’s when Granddad was still alive.

Mark: Yes. And Mama and Papa.

Helen: And Aunt Jessica

Mark: Yes.

Helen: And the dog. What was his name?

Mark: Her name. It was a female. Her name was Linda.

Helen (absently): That’s right, Linda.

Mark: Do you miss her?

Helen: Who?

Mark: Linda.

Helen (vaguely): Oh yes, certainly. We had a bird too, didn’t we? What was its name?

Mark (sullen): Linden.

Helen (clapping her hands in delight): Linden! Really? That’s delightful!! A wonderful name for a parrot!

Mark: It was a budgie.

Helen (brightly): Are you sure?

Mark (crossly): Of course I’m sure.

[There is another lengthy pause]

Helen (resignedly): Well, it doesn’t matter.

Mark: No. Not now.

(curtain)

Play #75: The Phantom Gardener

The play is set in a Horticultural Heaven—a subsidiary of the Greater Heaven. The Heavenly Gardener, Saint Herbaceous, sits at a high desk. He holds a golden trowel in his hand. Before him, quaking in his sneakers, sits a little man in spandex shorts and T-shirt. He carries a small pair of rusting secateurs.

Saint Herbaceous (outraged): …You mean to tell me you would sneak into a garden that was not your own and prune the shrubs—without the owners’ knowledge?

Phantom Gardener (trembling with fright): Yes.

SH: Tell me, what would you do, on a typical pruning trip?

PG (thinking back): Well, this year, I pruned a Quince, a few roses and a Rose of Sharon bush.

SH (furious): Numbskull !! You don’t prune quinces or Roses of Sharon!! And according to our source, you cut the rose bushes back almost to nothing!

PG (abject): I did what I thought best.

SH (with heavy sarcasm): And how often would inflict on this unsuspecting garden the supposed benefits of your great garden wisdom?

PG (thinking back): Once a year. Every autumn.

SH: Why would you do such a thing?

PG: (in a small, shaky voice): Well, you see, Your Greenness, I used to work for the garden’s former owners, and I’m not at all certain the present owners know much about the gardening at all!

SH (irritated): That’s not what I hear. As I understand it, the present owner of the garden is a very capable—indeed inspired—gardener! And she is understandably dismayed to find evidence, every spring, of the cutting and trimming you have taken upon yourself to undertake! It is NOT your garden. Indeed, it never was!!

PG (humbly): I still think I know best about that garden.

SH (outraged): Well I say you know nothing at all about it—and deplorably little about any kind of gardening!!

[The Phantom Gardener is now silent and afraid]

SH: You must now be chastised—in a way that will hopefully do some good.

PG (terrified): And what would that be, all Green-Knowing One?

SH (with crushing finality): You will wear a gigantic pair of heavy iron secateurs around your neck for the rest of your life! And you will never again visit that garden you have so selfishly pillaged over these past few years. [addressing the garden-guards who are waiting offstage] Now take this miscreant away to be fitted with that great weight of his own devising!!!!

[The Phantom Gardener is led away]

SH: I must now find a way to make reparations to the garden’s distressed owner. Perhaps I’ll send her a dozen rare everblooming rose bushes. Yes, I think she’d like that. And perhaps a Quince that bears solid gold berries in the early spring.

(curtain)

Play # 74: Cupid Stung By Bees

The play, which is derived from a painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder called Venus with Cupid Stung by a Bee (1532), is set in a small decorous wilderness—a tidy tempered forest—not far from a small German city. Venus naked and serene, is strolling among the trees, accompanied by a plump little cupid, who floats around her like a pink balloon. It is a sunny summer afternoon.

Cupid (hovering in the still air, suddenly alert): What is that buzzing?

Venus (languidly): Birds perhaps.

Cupid (surprised): Birds? Do birds buzz?

Venus (abstractly): I don’t know…do they not? I’ve forgotten.

Cupid: I bet they’re bees!

Venus (quietly): Well, perhaps.

Cupid (giggling): And where there are bees, there may be honey!

Venus: Yes, perhaps. Whatever that is.

Cupid (eagerly, boyishly): The bees make it. Would you like to try some honey, Goddess?

Venus (almost alarmed): Me? Well, I don’t know. I don’t remember it. It’s something to eat, is that right?

Cupid (eager): It’s sweet like candy!

Venus (suspicious): Insect candy.

Cupid (even more eager): I’ll be right back [he flies up into the buzzing tree]

[The buzzing of the bees grows louder and there is a sudden affrighted cry from Cupid]

Venus (languidly alarmed): Are you alright, Little One?

[Cupid returns, holding a chunk of honeycomb in one plump hand. He is covered with bee stings. A few angry bees cling to him still]

Cupid (breathless, trembling from his ordeal, holds out the honeycomb for Venus to see): Look, Goddess. This is Honey!

Venus (wary): The bees didn’t seem very pleased about your visit.

Cupid (laughing): They weren’t. They’re still not!

Venus (dejected): And look at yourself! You’re covered with stings.

Cupid (happy to have demonstrated his valour): It was worth it!

Venus (dubious) I’m not at all certain it was. The bees have spoiled your perfect, infantile beauty.

Cupid (gaily): Have some honey. I got it just for you.

Venus (gingerly dipping he finger into the honeycomb and cautiously tasting the worrisome honey): Mmmmm.

Cupid (proudly, as if he’d made the honey himself): You like it?

Venus (smiling): It’s as delicate and gentle as a rainbow.

Cupid (happily): Ambrosia! Food of the gods!

Venus (smiling happily): Of the Goddess, rather. It’s much too fine for all those boisterous, rough-hewn gods!

Cupid (grinning): If you like. It will be our secret then

Venus (delighted): Yes. Just for us. Beautiful Venus Honey—just for the two of us!

(curtain)

INCLUDEPICTURE "http://beesinart.com/bia_artists/bia_artists/cranach_l_files/blocks_image_24_1.png" \* MERGEFORMATINET

INCLUDEPICTURE "http://beesinart.com/bia_artists/bia_artists/cranach_l_files/blocks_image_25_1.png" \* MERGEFORMATINET

Cupid, Honeybees and Pain: The Bee's Sting

Play # 73: St. Anselm and the Spring

The play is set in a walled garden, near Canterbury, England. It is a morning in early spring, and the garden is sparkling with newly bloomed flowers. There is a stone bench in the garden, upon which sits—rather solidly--the stalwart figure of St. Anselm, sometime Archbishop of Canterbury.* A little girl plays innocently nearby.

Girl (bouncing up to the sedentary saint): Good morning, Stern Father of the Church!

Anselm (regarding her sternly): You ought to be at your prayers.

Girl: I’ve been at my prayers, and now I’m playing amongst the flowers! Aren’t they beautiful!!

Anselm (sternly): They are sent to lead us astray.

Girl (puzzled): Astray? [she looks around]. But we are in a walled garden. You can’t get lost in a walled gardcn!

Anselm (even more sternly): Yes you can.

Girl (cheerfully): Only if you really want to, I bet!

Anselm (smiling despite his wish not to): Wise beyond her years.

Girl (unperturbed): Are you enjoying the warmth of the sun? Isn’t it lovely!!??

Anselm (with a certain finality): The sun lulls us into complacency. Its warmth is a snare.

Girl: And so many flowers!

Anselm (sternly): Too many.

Girl: Look! Lovely blue Irises!

Anselm (almost fearful): Their blue will burn you.

Girl: And look, primroses!

Anselm: Baubles paving the way to perdition.

Girl: And brave Forget-me-nots!

Anselm: Ironically named flowers! Their very purpose is to make you forget!

Girl (puzzled and disappointed): Forget what, Holy Father?

Anselm: Your place under heaven.

Girl: I don’t think so, Venerable One. I know my place under heaven. It is to play amidst the new-bloomed flowers in this paradise-garden.

Anselm (brooking no nonsense): Things are harmful in direct proportion to the number of senses they delight. This garden is therefore a hotbed of sensory dangers. There are too many blossoms to see, too much fragrance to breathe in, too much warm stone to touch, too many singing birds to hear—and too much childish prattle to try to ignore!

Girl: How alive you must be, Holy Father, to do so much denying!!

Anselm: Nature must not be simply enjoyable. Nature is a manuscript from which we are required to read sobering truths.

Girl: Well, I wouldn’t know about that, stern Church Father. I don’t know how to read yet. Maybe when I learn, I can then become as sad as you are!

Anselm (risking a faint smile): Let us hope so, my dear.

(curtain)

* Anselm was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093-1109 A.D.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)